Just as EDM is being treated like a valid genre, its music videos are beginning to experience recognition. Deadmau5, in his cover story for Rolling Stone, spoke about his just-released music video “Professional Griefers.” Reportedly, “Professional Griefers” is the most expensive EDM video ever, with Joel Zimmerman contributing seven figures toward the endeavor. “Not to be all Kanye on you,” he said, “but this is one of the highest-budget electronic music videos of all time.”

Just as EDM is being treated like a valid genre, its music videos are beginning to experience recognition. Deadmau5, in his cover story for Rolling Stone, spoke about his just-released music video “Professional Griefers.” Reportedly, “Professional Griefers” is the most expensive EDM video ever, with Joel Zimmerman contributing seven figures toward the endeavor. “Not to be all Kanye on you,” he said, “but this is one of the highest-budget electronic music videos of all time.”

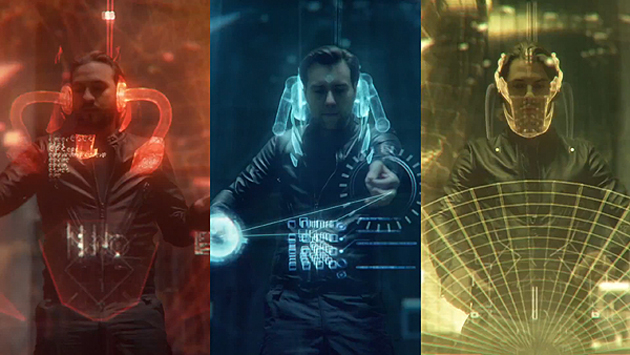

Does it show? “Professional Griefers” is an anomaly in the scope of EDM music videos, as it prominently features the DJ along with its featured performer, Gerard Way of My Chemical Romance. Beyond this distinction, “Professional Griefers” symbolizes excess without the tired bottle-popping scenario. A fight, between two animatronic mice-robots, one controlled by Zimmerman and the other by Way, is the plot, and from the fights to the robot-cat, the video is slathered in dazzling computer animation. The extensive crowd and scene changes show that, yes, a budget went into it.

“Professional Griefers” additionally symbolizes the large trajectory Zimmerman’s career has followed since he broke out of as a DJ and producer. Gone are the days of “Ghosts N Stuff” – which, for those that can’t remember, featured a man in a sheet, regardless of symbolism or plot, wandering around town.

The videos of Zimmerman’s contemporaries are still stuck in the same rut, despite that MTV just introduced its first Best Electronic Dance Music Video category for the VMAs. Otherwise, how else can you explain why Avicii’s excellent “Levels” tune is met with such a wretchedly cheap music video?

Dancing for a Budget

No matter the artist, from New Order or Inner City to Avicii, electronic music videos go through a cheapness phase, which is encapsulated by a single theme: dancing crowds.

It’s a logical explanation. From New Order’s breakbeat effort “Confusion” to the club-centric videos from the early part of Tiesto’s career, music plays and people dance, perhaps accompanied or accented by lighting or graphics. New Order’s “Confusion,” their follow-up to the video-less “Blue Monday,” captures the club scene of the early 1980s, from the Funhouse Disco to the guest appearances of producer Arthur Baker and Jellybean Benitez. Inner City did this on a smaller scale, recreating the club atmosphere for “Big Fun.” Pop acid house music videos from S’Express and D-Mob can be boiled down to raving on a soundstage.

In modern times, lesser-promoted singles are still given the same video treatment: shots of the DJ in the booth or the excited, dancing crowd. From Tiesto’s “Adagio for Strings” to Cascada’s library dancing of “Everytime We Touch” to the original take for Avicii’s “Silhouettes,” this scenario becomes overused. But, unlike capturing a moment in time, these modern instances are lackluster productions.

Pop Equals Plot

What happens when an artist hits it big? Greater awareness translates to a threadbare, if not tangible, plot. New Order’s performing- or club-themed music videos transformed into the psychedelic, trippy scenarios of “True Faith” and “Fine Time,” and every MTV VMA nominee’s offering is graced with a story arch; Calvin Harris’ winning “Feel So Close” even leans more toward the faux-Americana of a Lana Del Rey video. EDM, in these cases, transforms from “Everyone, get up and dance!” to the soundtrack of a scene – even the berserk office worker of “Levels.”

As the New York Times just reported that big-name producers, like Skrillex and Kaskade, are gravitating toward movie scores, creating a mini-film through a music video is another step closer to this more serious endeavor.